Bitter Harvest: Cassava and Konzo, the Crippling Disease: Part II

Part II: A Real Love Story

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO—One afternoon in 1998, a healthy 18-year old named Gaby Ngabu Kasongo was hiking home from the farm, when boom: His legs froze. “It’s as if my muscles suddenly turned into blocks,” he says. Konzo, a paralyzing disease caused by gradual cyanide poisoning, hit him like a brick. Several of his neighbors in the Democratic Republic of Congo had fallen victim too. None of them could afford bicycles, never mind cars, motorbikes or wheelchairs, so konzo meant they were stuck. “I cried, I said my life is over. I can’t go to church, I can’t farm, I can’t go to school. And my dominating thought was, I will never have a wife,” Kasongo confesses. “Every night I went to bed in tears.”

In konzo’s mildest form, both of a person’s knees or ankles twist and spasm. More severe cases mean paralysis from the waist down. Because the disease primarily afflicts those living on less than $2 a day—people who have no way earn money outside of farms or mines—konzo renders them dependent on others and often depressed.

It would be years before Kasongo learned that konzo is caused by a bitter variety of cassava (Manihot esculenta). It’s a staple crop with starchy white roots as thick as potatoes, which some 600 million people around the world rely on for food. Bitter cassava is the most drought-resistant variety. It outlives other crops. However, it produces high amounts of two cyanogenic glucoside compounds when it’s grown in parched soil. When consumed, those break down to release hydrogen cyanide at concentrations dangerous to people.

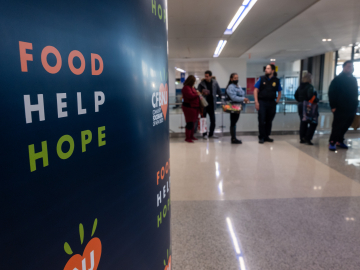

Hydrogen cyanide can be combatted, however, through two means. If the roots are soaked in water for several days, the compounds degrade. In parts of Africa, women regularly leave the roots in rivers with a sign post marking the goods as their own before they dry out the roots and grind them into flour. But for various reasons, this process does not always happen. “I remember that sometimes we just chewed on [the roots] because we were so hungry,” Kasongo recalls. “The cassava was so bitter it felt weird on your tongue.”

A woman retrieves cassava roots that have been soaking in a stream outside of Kahemba. Image by Neil Brandvold

People from eastern Congo told me they hadn’t soaked the roots either. The region has been plagued by armed conflict for more than 2 decades, and in attempt to hide their food from roving militias who steal it, villagers eat their cassava immediately or take it on the run.

The second mode of defense is decent nutrition. As long as a person has enough protein in their diet, amino acids convert cyanide into thiocyanate, a less toxic substance excreted in urine. Konzo shares this requirement for malnutrition with other neurotoxic diseases caused by organic, non-GMO, fully edible plants. For example, people in Guam diagnosed with “Parkinsonism”—a condition that causes tremors, impaired speech and muscle stiffness—acquired the ailment from exclusively eating seeds of the “false sago palm,” Cycas circinalis, when other food was scarce. In India, a disease called neurolatyrism—characterized by spastic, partial paralysis of the lower limbs—surfaced during droughts when people ate the hardy grass pea plant, Lathyrus sativus, and little else for prolonged periods of time.

Likewise, Christopher McCandless, the young hiker documented in the book “Into the Wild” by Jon Krakauer, appears to have succumbed to toxins in the wild potato, Hedysarum alpinum, because he had little else in his diet. Edible for well-nourished people, the plant may be lethal for those suffering from malnutrition. McCandless had decided to leave behind the comforts of modern American life to survive off the land. In contrast, Kasongo had no choice. Bitter cassava was all he had.

Soon after Kasongo collapsed, his father brought him to a traditional healer who wrapped his legs in bark. When that didn’t cure the condition, the healer cut his legs and rubbed a traditional mixture of salt and chili powder into the wounds. After a few months of the treatments and little improvement, his father raised money to send his son to a hospital in the capital, Kinshasa. The trip is just 120 miles as the eagle flies, but the lack of roads and vehicles means the journey can take weeks.

With two walking sticks, Kasongo hobbled for several hours to the closest town, Popokabaka. From there, the son of a pastor traveled with him on a canoe up the Kwango River. They slept under the stars on the riverbank. At a highway bridge, they waited for a ride. A truck driver allowed them to join dozens of other hitchhikers riding atop the cargo, as the truck teetered precariously through the mountains. At midnight, they arrived in Kinshasa.

In the capital, Kasongo visited nuns at a missionary hospital who massaged his legs with balm. “But there was no improvement, and they insisted on a high price,” he recalls. “When I spent all of the money provided by my father and the pastor, I could no longer see them.” His aunt, who lived in the city, convinced him to stay by finding him a job in a tailor’s shop.

Gaby Ngabu Kasongo sewing a dress. The effects of Konzo make it difficult for Gaby to work long hours. He says his hands begin to get stiff and hurt when working. He also struggles to use his legs to operate the sewing machine. Image by Neil Brandvold

One morning on his way to church, Kasongo spotted Grace Neema Bandole. She was short like him and had a broad, welcoming smile. They began to talk and soon Bandole was helping Kasongo cook and clean. However, when her father met Kasongo and saw how he struggled to walk, he forbade the relationship. “He was thinking that Gaby couldn’t provide for me, that he wouldn’t be strong enough to work and that his daughter would suffer,” she tells me. We’re sitting in Kasongo’s dim one-room house. A sheet hangs in the middle of the space, separating his mattress from a few stools, tin plates and a laminated poster of a mansion with a red Corvette in the driveway.

Bandole sits on the front stoop in a beam of light and recalls their courtship. Her father moved the family across Kinshasa when he found out that she had continued to see Kasongo despite his disapproval. Still, she’d sneak back to his place. And when her father learned of this disobedience, he threatened to return her to the village in eastern Congo that the family had fled because of ongoing war. “I told my father, ‘You better bring a tank and soldiers to tie me up and put me on a truck, because I will not leave Kinshasa willingly.’” Her father relented.

A couple of weeks ago, Kasongo’s father came to Kinshasa for a ceremony to formalize his son’s engagement. Kasongo hands me a photo album from the affair. In one picture, a man holds a list of items that Kasongo must provide if he’s to take their daughter’s hand in marriage: A pot, a thermos, a sheep or goat, a jerry can, bed sheets and a dowry. He hopes to acquire enough money to fulfill the requests and marry his love. Beyond the romance, Kasongo confesses he needs her daily help. For example, he cannot lift a bucket of water to bathe. Like his neighbors in this shantytown, he has neither running water nor electricity.

Kasongo is lucky to have made it to the capital in his condition. Many people with konzo go unnoticed by medical science, which is why it’s near impossible to know the true burden of the disease. Nearly 11,000 cases of konzo have been officially reported from the DRC, Mozambique, Tanzania, the Central African Republic, Cameroon and Angola, according to a 2011 report in the journal PLOS Neglected Diseases. However, the authors acknowledge that the true caseload may be far higher. For example, unofficial reports estimate that 100,000 people have suffered from konzo in the DRC alone. And in the eastern region of the country, where the Congolese neuropsychiatrist Daniel Okitundu works, new cases steadily emerge.

“So many people in eastern DRC are not known because they cannot move from their village to town centers,” Okitundu tells me in an office in Kinshasa. “And because they think konzo is sorcery, they go to healers and church rather than seek medical care, which means there are no records of their condition.”

On one trip through eastern Congo, Okitundu met a nurse named Theodore Nabarhimba who walks with leg braces and crutches, due to a bout of childhood tuberculosis. From his own experience, Nabarhimba realizes that although a cure for konzo is nonexistent, physical therapy, employment and a sense of empowerment keep people with konzo alive. He’s taken many under his wing though his means are limited. “It’s so important to reinsert people into society,” Nabarhimba says.

With no cure for konzo, this inclusion into the social fabric of communities is essential. As is love. Just before I leave Kasongo’s tiny abode, he says, “If I had stayed in my village, I don’t think I’d be alive—my life would have had no significance.”

Bandole looks up at him from the front stoop, where she sits by his knee. He touches her shoulder and says, “Now in Kinshasa I have a fiancée who accepts me for who I am, I feel hopeful.”

Read the Intro to the Series and Part I, Desire's Antidote to Poison.

Special thanks to the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting for supporting photography for this series.

Join the thousands of subscribers who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues: Subscribe to GHN