The Global AIDS Fight Has a Data Problem

HIV researchers have long argued that to win the global fight against the disease, resources and programs must reach those most at risk of contracting and spreading it.

But services for such key populations (KPs) consistently lag behind HIV services for other populations. The result: worse treatment outcomes for men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender individuals, sex workers, and people who use injectable drugs.

Together, these KPs accounted for approximately 43% of new HIV infections in 2019, globally.

The Data Problem

Researchers say that major discrepancies in the data used to measure key populations is holding back efforts to design and fund sustainable programs to serve KPs.

Estimates on the number people in different key populations reported by the world’s leading HIV programs—PEPFAR, UNAIDS, and the Global Fund—vary by as much as 20X, according to a dashboard created to visualize the problem by a team at amfAR, the Foundation for AIDS Research.

“The results are scattershot—particularly around MSM, where we would expect to see a little more consistency across studies,” says Brian Honermann, deputy director of public policy at amfAR. “These are the results that policymakers are using to make decisions about the amount of funding to put into these programs, and how ambitious to be with the targets for those programs, and how many people need to be on treatment.”

For example, PEPFAR's size estimates for MSM in South Africa have swung from 1.2 million (7.64% of the adult male population) in 2015 down to 309,700 (1.9%) in 2023. PEPFAR's MSM size estimates in Zambia have gone from 7,443 (0.18%) in 2017 to 127,589 (2.7%) in 2023, showing how vastly size estimates can change over time. There are also wide regional inconsistencies: PEPFAR's current MSM size estimate in Malawi is only 11,614 (0.23%) suggesting rates of MSM in South Africa and Zambia relative to Malawi are 8 and 12 times greater, respectively.”

That discrepancy “doesn't really make sense, biologically or behaviorally,” says Honermann.

UNAIDS and WHO have acknowledged the discrepancies. In 2020, they recommended that countries revise their population size estimates if their figures indicated that MSM amounted to less than 1% of the total adult male population. As amfAR’s dashboard shows, dozens of countries fell under that minimum threshold in 2022, including Burundi, Ivory Coast, Ghana, India, Indonesia, and Kenya.

A Difficult Problem to Fix

Size estimates for KPs are “notoriously inaccurate and challenging to assess,” says Honermann. “They’re hard to do. They’re not well invested in, especially to do on a large scale.”

The problem is that typically data originate from small samples in urban areas being extrapolated to represent a whole country.

“This is really a hard area,” says Jennifer Kates, senior vice president and director of the Global Health and HIV Policy Program at KFF. Getting better data requires global will, she says. “Then there are concerns about safety, and putting vulnerable people in more vulnerable positions,” Kates says. “It has to be done delicately.”

These challenges are compounded by stagnating donor funding for HIV programs, rising anti-LGBTQ+ policies across the globe, and stigma and discrimination that discourage members of key populations from being identified as such—and even from seeking care at all.

The Data-to-Services Challenge

Persistent stigma and discrimination in care settings where demographic data is often gathered contribute to data gaps on KPs, says Refilwe Nancy Phaswana-Mafuya, a professor of epidemiology and public health at the University of Johannesburg.

This ultimately distorts evaluations of the country’s HIV efforts, she says.

Phaswana-Mafuya’s department works closely with the South African National AIDS Council, which manages and monitors the HIV response in a country that has which over 7.5 million adults and children living with the disease.

Her list of the numerous challenges in tracking key populations in South Africa includes the lack of a centralized system for collecting and reporting KP data as well as the fact there is no unique identifier for KPs in health information management systems.

A major problem is that available data are pushing leading programs toward “harmonizing HIV services with other health services” used by the general population—the kind that key populations tend to avoid, says Stefan Baral, a leading HIV researcher and epidemiology professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“We have to go out to where folks are because these folks are not coming into clinics … That runs counter to the idea of mainstreaming and centralizing services,” says Baral. “That’s where the tension is.”

In South Africa, 12% of people in key populations interviewed were not receiving health services anywhere, according to a 2023 report by Ritshidze, a community-led monitoring system. In addition, a significant proportion had been refused access to health services because they are from a KP. The report also found that drop-in and mobile clinics were friendlier to KPs and made them more comfortable.

While South Africa’s overall HIV incidence rate fell by 55% from 2010–2019, that progress doesn’t tell the whole story.

Showing a reduction in infections overall “is good in terms of numbers, but it’s not as impactful as if [the data] showed new infections among sex workers and their clients, or [MSM] and their partners”—even if those numbers for KPs show slower progress, Phaswana-Mafuya says.

Emerging Solutions

For her part, Phaswana-Mafuya’s team is working to solve her laundry list of data challenges by building a centralized data repository focusing on key populations “so that we’re able to do some integrated analysis and answer those questions that could not be answered before.”

The challenges of gathering data on KPs can’t be solved overnight, but in the meantime, says Honermann, as global HIV programs become increasingly data-driven, they must “have the humility to recognize that if the data are inconsistent, reliance on those data may lead to underfunding of programs. It may lead you in wrong directions.”

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues. https://www.globalhealthnow.org/subscribe

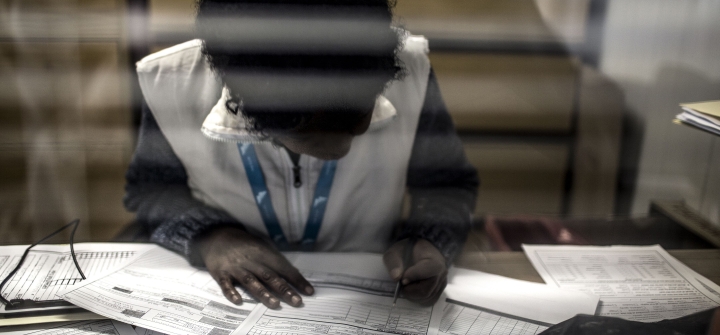

A peer educator of the Wits Reproductive Health Institute Sex Worker Programme sits in consultation with a client at the clinic in Hilbrow, Johannesburg, on July 20, 2017. Gulshan Khan/AFP via Getty