Flu Season in N. America: 5 Facts

Predicting what fast-mutating influenza viruses will do is never easy, but the evidence so far indicates that North America should brace for a bad year. Flu season, which can start as early as October and typically peaks in January or February, kills between 12,000 and 79,000 people in the US every year.

Here are 5 things you should know.

1. The flu will likely batter the Northern Hemisphere this year.

The Southern Hemisphere can serve as a barometer for what might be coming north. The bad news: This year, there’s been very strong flu seasons in Australia and across parts of South America.

Part of the reason it’s been hard down south is that this year’s vaccine isn’t a perfect match for the viruses circulating there now. The flu virus mutates frequently. In this case, at least one of the flu virus strains may have undergone antigenic drift. This means that its surface proteins have changed, making it harder for antibodies launched by the vaccine to neutralize the virus.

So, the virus down in the Southern Hemisphere is changing, mutating, and, now, it's coming in our direction. Our concern is that those viruses will migrate and be the ones driving this year’s flu season in the Northern Hemisphere.

2. This year’s flu vaccine for the US doesn’t look like it will be a perfect match for viruses circulating, either.

We decided on the 4 virus strains that make up the US flu vaccine in March 2019. We have to decide so far in advance because it takes about 6 months to make a large enough batch of vaccines for immunization campaigns. (Most flu vaccine strains are grown in chicken eggs—a lengthy process.) So, the vaccine strains have to be chosen based on the viruses that circulate in the previous flu season.

There’s not enough time to see what viruses are circulating in the Southern Hemisphere before determining the Northern Hemisphere’s formulation..

3. People still need to get their flu shots.

Even if one of the vaccine strains isn't a perfect match, growing evidence suggests that vaccination significantly reduces the severity of influenza. While it may not keep you from getting the flu, vaccination has a higher likelihood of keeping you from getting hospitalized by influenza.

Plus, the vaccine is safe. Numerous, numerous studies have shown the vaccine is safe.

4. The long lead-time for vaccine manufacture is baked into the current process.

The primary vaccines used in Northern Hemisphere are grown in embryonated hens eggs. That process is just time consuming. First, not all flu strains grow well in eggs. A significant amount of time is invested picking strains that are both circulating in humans and can also grow in eggs. Then, the entire process of generating the vaccine in eggs takes a lot of time. So, you need 3 or 4 months to just grow the vaccine and process it from those eggs.

That means a roughly 6-month window that's needed to identify a strain and make enough vaccine from that strain to start a vaccination process.

5. There’s hope for a better vaccine.

The NIH recently announced a huge multimillion dollar effort to rethink the flu vaccine from scratch and come up with a vaccine that can induce stronger and longer immunity and one that reacts with many more strains. It’s called a universal flu vaccine. The US government has also initiated a study to find ways to improve the current production of influenza vaccines. These are both needed to help improve our ability to counter influenza.

Multiple laboratories are investigating ways to generate more effective and longlasting immune responses to vaccination. So, ultimately, you would only have to get a flu shot every 5 years, and it would be much better at protecting against all these different sub-strains that emerge.

Am I optimistic? I'll punt by saying the next couple of years are really going to be critical because investigators are now starting to go into the early phase human trials to see how some of the vaccines that seem to work really nicely in our animal models will work in humans.

Andrew Pekosz, PhD, is co-director of the Johns Hopkins Center of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance and a professor of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Join the tens of thousands of subscribers who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues: http://www.globalhealthnow.org/subscribe.html

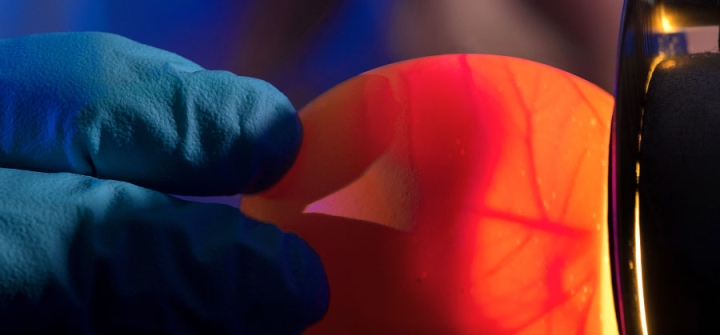

A CDC scientist demonstrates a lab technique called “candling,” to gauge the egg's suitability for use in growing flu viruses. Image: CDC/ Robert Denty