Beyond Mosquitoes: Sexual and Reproductive Health in Zika's Wake

RECIFE, BRAZIL—By August 2016, just over a year after the Zika virus epidemic began in Brazil, the number of live births in Pernambuco declined by nearly 10%, according to a study released in June 2017. Between August and December 2016, 15,000 fewer live births were recorded than in the previous year.

This is not an inconsequential decrease, nor is it likely attributable to random factors.

The northeastern state of Pernambuco, where the Zika outbreak was first detected, was also one of the hardest hit by the virus. In 2016, the state represented 18.9% of all congenital Zika syndrome (CZS) cases in the country.

Of course, the Zika epidemic may not be the sole driver of the 10% decline; instability caused by other factors, such as the political and economic crises in Brazil, may have also played a role. The combination of variables that triggered the decrease in live births is not yet fully understood, but the theories under investigation provide insights into sexual and reproductive health in Brazil during and after the Zika epidemic.

DURING THE ZIKA EMERGENCY

The same study that reported the 10% decrease in live births also investigated changes in reproductive attitudes and practices that may help explain the decline. Letícia Marteleto, PhD, an author on the paper, noticed a marked disparity between social strata on control over reproductive intentions. Given the alarm around fetal transmission of Zika and adverse birth outcomes, both high- and low-socioeconomic status (SES) women expressed desires to postpone pregnancy during the Zika epidemic—but only wealthier women had confidence in their ability to do so.

Marteleto explained further: “Lower SES women not only have a harder time accessing different forms of contraception and information on how to use it consistently and correctly, but they also have less bargaining power with their partners.” Poorer women equally appreciate the risks posed by Zika, but have fewer resources and face larger barriers in improving the effectivenesss of their family planning practices. Financial constraints generally force them to depend on the overburdened public health care system, which tends to offer limited contraceptive options and inadequate counseling—whereas wealthier women can often afford to purchase contraceptives at private pharmacies and negotiate use with their partners.

In line with this, the decline in live births was largest among higher-SES women. However, Juliana César, an NGO Gestos project advisor, pointed out that there are not enough people in Pernambuco’s middle and upper classes to account for the entire 10% reduction—which leads to the blacklisted topic of conversation: abortion.

Abortion is illegal in Brazil, except for in cases of risk to the mother’s life, rape, incest, or fetal anencephaly. Information on induced abortion rates in the past year are virtually non-existent, since the health surveillance system collects no official data on this. However, for years, it has been widely known that the ban does not eliminate abortions; on the contrary, it forces women to undergo clandestine and often unsafe procedures. An estimated 1 in 4 pregnancies in Brazil are terminated, and abortion-related deaths are the fourth leading cause of maternal mortality—with young, Black, and poor women suffering the highest death rates. Moreover, women across class lines in the Marteleto et al. study reported a willingness to have an abortion if infected with Zika virus.

While the lack of quality data and reluctance to discuss the topic muddy this area of inquiry, it is very possible that an increase in abortion contributed to the decline in live births. For one, Women on Web, a nonprofit online service that provides abortion medications to women who cannot safely access them in their home country, reported a 108% increase in abortion requests from Brazil following the PAHO epidemiological alert regarding Zika.

At a discussion of the study’s findings, Sandra Valongueiro Alves, MD, PhD, MS, co-author and researcher at Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, said she has not found an increase in hospitalizations for abortion-related complications, which is what might be expected if induced abortions were on the rise. Nor was there an increase in all-cause maternal mortality in 2016. However, discussion attendees noted that these data do not necessarily invalidate the possibility that the abortion rate grew. César suggested that the lack of hospitalizations could be due to a lack of complications, with women seeking safer methods. Another researcher in the audience agreed, adding, “maybe women are aborting earlier in their pregnancy, when there is a lower risk of complications.”

Luciana Caroline Albuquerque Bezerra, PhD, MPH, executive secretary of health surveillance in Pernambuco, said, “when the boom first happened, Zika infections were widespread and there was no SES difference, but then microcephaly cases did show a class differential. We know that the higher class have more means of preventing pregnancy, and we wonder if abortions increased in the private sector. It’s hard to say what happens in private hospitals.”

Even for those who have not personally undergone an induced abortion, the fear of indictment for having secondhand knowledge of criminalized activity keeps many from speaking on the record about the topic. An official who asked not to be named said that the demand for misoprostol in the black market has surged since the start of the epidemic; another anonymous source acknowledged awareness of wealthier women accessing surgical abortions.

Paula de A.L. Viana, of the sexual and reproductive health NGO Groupo Curumim, told me that callers asking for abortion assistance—which the organization legally cannot provide—inundated a hotline they launched during the outbreak to provide reproductive health support. Many of the mothers I interviewed shared similar stories about other people seeking abortions, though none attested to having one themselves.

2 court cases filed before the Federal Supreme Court during the height of the Zika epidemic have demanded expanded access to legal abortion services. As of October 2017, both remain pending.

AND AFTER THE ZIKA EMERGENCY

Lingering barriers around effective contraceptive use have a hand in the country’s unplanned pregnancy rate of as high as 54%. Many groups, from academics to advocates to intergovernmental agencies, lambasted the Brazilian government for its narrow focus on mosquito control and failure to address gaps in reproductive and sexual health rights as a core component of the official response.

But what about now, with the Zika epidemic’s emergency status rescinded and new infections waning? The Marteleto et al. study sheds light on reproductive intentions and behaviors during the peak of the epidemic, and my interviews with mothers of children with CZS explored some of the same questions, under different circumstances—in the aftermath of the emergency.

Almost none of the mothers I met who are raising children with CZS expressed a desire—or ability to provide for—additional children. Even those who had not achieved their desired family size acknowledged that the financial, emotional, and labor demands of caring for a child with CZS had shifted their plans, though few recalled receiving any postpartum counseling on how to also shift their practices.

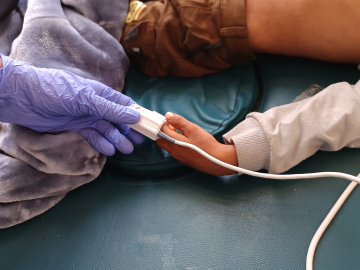

Mylene Helena dos Santos Ferreira, 23, showed me the box of oral contraceptives she was taking when she unintentionally conceived Davi, her 2-year-old son with CZS—they are the same pills she currently uses. Dhulha Alen Silva do Nascimento, 25, became pregnant in February 2016, only a few months after giving birth to Valentina, her daughter with CZS. She mistakenly thought she was in the period of postnatal infertility and was not using contraception, only to be shocked when she learned she was pregnant. At 3 months, she had a spontaneous abortion that she described as “devastating.” She now pays for a monthly injection at a private pharmacy. Their narratives reflect the findings of Human Rights Watch, which reported that women often experience contraceptive failure or discontinuation, leading to unintended pregnancy.

Like many mothers I met, Ferreira and Nascimento would like to receive a tubal ligation, a sterilization procedure that would help guard against future unplanned pregnancies. Neither has had the surgery so far. Brazil’s 1996 Family Planning Law qualifies access to voluntary sterilization by requiring that the individual be at least 25-years-old, or have a minimum of 2 children. But University of São Paulo School of Nursing Professor Ana Luíza Vilela Borges, PhD, MPH, said, “Many health care providers themselves don’t understand the law, and over time it has become the norm to start requiring that the person be 25 years of age and have at least 2 children, when actually it is ‘or’.”

Moreover, the law decrees that “in the life of a married society, the sterilization depends on the express consent of both spouses.” This condition is discriminately enforced, according to Viana from Grupo Curumim. “No wife is ever asked to sign if the husband is getting a vasectomy,” she said, “but the man has to give his permission if his wife wants to be sterilized.”

Thus, although sterilization is technically offered through the public health care system, gaining approval for the procedure proves to be a challenge. “Even if the woman meets the criteria, no one is really willing to do it,” said Borges. “This is what we mean when we say that our reproductive health rights are not being respected. It’s a really controlling environment.”

When I asked why they had not pursued sterilization given their desire for the procedure, Nascimento said she “didn’t want to put in all the effort to convince a public hospital doctor.” At a private clinic, she received a quote of BRL1800 (US$570), far beyond her financial means. “And anyways,” she said, “even if I did get the surgery, who would take care of my children while I recovered?” Ferreira felt her young age would hinder her chances for approval.

Viana supports lifting restrictions on sterilization, though she maintained that there should be a waiting period for tubal ligation after delivery to allow the womb to return to its natural state and to account for the possibility that the baby might die in the first few weeks of life, which can lead to regret among women sterilized immediately postpartum. There is also an ethical dimension to consider, with tubal ligations vastly outnumbering vasectomies due to gender power imbalances and a history of politicians exchanging the procedure for electoral votes.

Instead of focusing on sterilization, Bezerra said the government has “decided to concentrate its efforts on publicizing and promoting IUDs,” long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) used negligibly in Brazil—comprising less than 2% of the method mix. Borges and Viana are vocal advocates of authorizing nurses to perform IUD insertions—a procedure currently limited to physicians, which they believe creates workforce shortfalls and limits access to the contraceptive. Though LARCs boast many benefits, including low failure rates, many health care practitioners warned that expanding long-acting methods should not come at the expense of condom promotion, espeically given an uptick in syphilis cases in Pernambuco and the potential for sexual transmission of Zika.

While the Zika emergency exposed fault lines in sexual and reproductive health rights in Brazil, it also offers an opportunity for the government to begin mending inequities. As the legacies of Zika continue to unfold, many will be watching to see if rights are advanced, or further diminished.

See also the GHN exclusive photo essay by Poonam Daryani, The Other Children in Brazil’s Zika Epidemic, and her video slideshow, A Month with Mylene.

Poonam Daryani received her MPH from Johns Hopkins University in May 2017 and is currently a Clinical Fellow with the Yale Global Health Justice Partnership. Her reporting for this story was supported by the Johns Hopkins-Pulitzer Center Global Health Reporting Fellowship.

Interpretation was provided by Rafael Alkalai, Tiago Cabral, Adriana Bentes dos Santos, and Margarida Corrêa Neto.

Join the thousands of subscribers who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues: http://www.globalhealthnow.org/subscribe.html

Neighborhood on the outskirts of Recife, Pernambuco, where Mylene Helena dos Santos Ferreira, 23, lives with her 3 sons, including her youngest, born in August 2015 with congenital Zika syndrome. Image by Poonam Daryani, BraziI