"A Really Big Change": Global Health Leader Marian Wentworth

When Marian Wentworth took charge of Management Sciences for Health in March, the global health NGO had been through a rough few years. It had shed a third of its workforce after some large contracts ended. Her top priority was making sure MSH was "was right sized or healed from its right sizing," Wentworth says.

Now, she says, “I see a lot of things actually swinging into MSH's sweet spot. I'm really optimistic for MSH's future.”

As she settled in to being MSH’s president and CEO, she's relied on 3 trademarks of her leadership style: Candidness, transparency and having a diverse leadership team. “I'm more likely to have a hodge-podge of different folks on my leadership team than a bunch of people that look like mini-me’s,” says Wentworth, a former vice president of global vaccines strategy for Merck.

In this second part of her Q&A with GHN, Wentworth discusses the challenge of a project-based business, her transition from Merck to the nonprofit world, and advice for students interested in global health.

Read the first part of the Q&A with Wentworth here.

You were named president and CEO of MSH back in March. How has that transition been for you from being a vice president at Merck to heading into this large NGO.

It's much more about delivery of care and delivery of services than about selling products. I completely love it. I'd been able to change and grow many times at Merck, but you get to a certain level and you start running out of possibilities to make really, really big changes. This one is a really big change.

I love working in an NGO environment. I like the fact that I can be passionate routinely and it doesn't compromise my authority. When you're in a corporate board room, especially as a woman, you've got to do a lot in order to make sure that you convey authority. I don't have to try hard [here]. It's a different environment. It's a much more cooperative environment. The challenge isn't getting people to listen to you because you're the boss. The challenge is to get people to listen to each other so that they work with each other as effectively as possible.

Did you have to overcome skeptics who might have thought, "Oh. This person was a vice president at Merck. She won't understand us."

Almost none.

Really?

I was surprised. In fact, there were a lot of staff here who were completely enthusiastic before I had earned a wit of it. Because I was female and because I was private sector. Those 2 things seemed to be great. Every now and then when I dig, I'd find somebody who's nervous. Are we trying to turn into a for-profit? Because I do pay attention to the dollars and cents. I pay attention to them for the same reason I pay attention to them at home. Not because I want us to be wealthy but because I don't want us to have to worry about how we're going to pay the rent.

What's been the biggest lesson that you've learned so far?

The value of passion. It really is a good thing to be passionate, to show passion. It doesn't necessarily undermine your authority. I think the other surprise is that I've spent a fair amount of time trying to add a bit of professionalism or business discipline to a few things. Not because I want to turn us into a Merck—[or] even a for-profit Beltway bandit kind of organization. That's not the goal. We're MSH. We do what we do.

How would you describe your leadership style?

I'm pretty transparent. I'm pretty candid. I really like a leadership team that's highly diverse in terms of mindset and style and thought, because tough problems require bringing together different points of view. I'm more likely to have a hodge-podge of different folks on my leadership team than a bunch of people that look like mini-me’s.

How do you, as a leader, get everybody on the same page? How do you get your arms around an organization that's so big?

There are a couple things. Step one is to actually have a high functioning leadership team. Diverse talent, discussing tough issues, but then locking arms on how we're going to approach them. One of the things I've noticed throughout my career is that if you establish that kind of model at the top, that it will propagate.

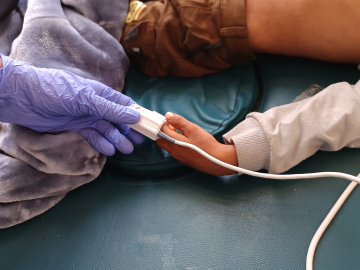

The other is ... I blog weekly. I also instituted a monthly email series. I'm committed to traveling three to four times a year to our most remote projects. Three times a year we do ... They're called staff meetings, but they [are] broadcast. Then we do project reviews, of course, more routinely. I try and attend those where I can.

When you decided to take this job, did you come to it with certain goals for the organization, specific things you want to achieve here?

Yeah. I knew this organization had gone through a pretty difficult time with a number of large projects closing all at the same time. My goal was actually first to make sure that the organization was right sized or healed from its right sizing.

I just needed to make sure that we were living within our means and at our size in an effective kind of way. That's an operational target. We're almost there.

The other was we'd been focused for a long time on one large donor and we really do need to diversify. The teams are already well on their way to that too. We've won awards from new donors. We will be announcing more over the next few months. I'm very excited about that.

I'm assuming a lot of MSH's work is project-driven. Specific funding for specific projects.

Yeah.

How do you keep the human resources together when those projects go away?

That is the most painful part of running project-based businesses. We're right now, I don't know, 1,700, 1,800 people. Few years ago we were 2,700 people. That doesn't actually even tell you about all the turnover. We've started new projects or we've hired people and we've closed other projects where we're ... It's more than a thousand people different over two and a half years.

Wow.

Our employees understand we're in a project-based business. It's painful. We don't like it. I have conversations with folks who are frustrated on a regular basis. It is part of what we do. Another reason why we'd love to find a few more things that can soften the blow a little bit. I really view MSH as more of a community than a set of employees. We have a database of more than 100,000 people. When I go to meetings anywhere in the world, I will meet people who used to be at MSH. It's still a community.

What would your advice be to students who are interested in global health?

First of all, congratulations. I don't think there's any greater calling than to try and make the world healthier.

You have to be prepared for frustration. I think building your own internal resilience is a hugely important.

Starting early to have at least a definable skill and then over time broadening out so that you're more flexible across more spaces. Amassing a diversity of experiences. Knowing yourself. If you're the sort of person who is just quite a generalist or quite a specialist, then don't try to be what you're not because that will show.

Any last thoughts?

I was talking about MSH in terms of getting into our size. I do actually think that we will grow again over the next couple of years because the work we're doing seems to be taking hold and seems to be making sense to more places. The pendulum swings a little bit in terms of what kinds of organizations do the development work, whether the development work is more vertical and diseased focused, or whether it's broader. I see a lot of things actually swinging into MSH's sweet spot. I'm really optimistic for MSH's future.

Join the thousands of subscribers who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

Marian Wentworth visits the Soroti Regional Referral Hospital in Mbale, Uganda. (Image: Warren Zelman/MSH)