Global Health Security Starts with Countries

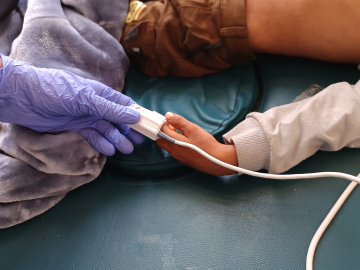

In September 2017, the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control faced an outbreak of monkeypox—a disease unseen in our country for nearly 40 years. The skin rashes, swollen lymph nodes and other symptoms of this “cousin to smallpox” caused great concern in communities. Misleading front-page headlines like “A new airborne Ebola-like viral disease, referred to as monkeypox has hit…” did not help.

We responded quickly by activating an emergency operations center, deploying rapid response teams, and launching intensive surveillance and community mobilization. Our colleagues at the US CDC supported our efforts with laboratory diagnosis as did our partners in the Institut Pasteur in Dakar, Senegal. Within a month of confirmation of the first cluster of cases, the US CDC provided technical support so that the NCDC National Reference Laboratory can now test for monkeypox in less than 24 hours. The outbreak ultimately included 122 confirmed or probable cases in 17 states and 7 deaths, as we documented in a recent Lancet article.

Despite our best efforts, 2 cases of monkeypox from Nigeria were reported in the UK in September 2018. Subsequently, 2 more cases with travel history from Nigeria were reported in Israel and Singapore.

We were fortunate that the virus wasn’t more lethal, however the spread of monkeypox to 4 countries within 2 years highlights the urgency of collaboration for global health security.

“Global health security” is not just a trendy term, but a global need. And it starts, in my opinion, with health security in individual countries. I make this point in a chapter I contributed to the 2019 annual report published by Dame Sally Davies, chief medical officer for England. Dame Sally chose to focus this year’s report on England’s engagement in global health issues. When presented with this unique opportunity, I chose to highlight the importance of national health security as the basis of global health security.

Our experience with monkeypox underscores the need for countries to strengthen their national health security infrastructure. What does this mean? Countries need to develop and scale up improved prevention, detection and response to infectious disease threats. To do this, they need to build well-funded national public health institutes that incorporate surveillance and response to all infectious diseases. Over the last 3 years, NCDC has received a legal mandate through an act signed into law by the president of Nigeria. While our funding has also increased, there is still a lot to be done to provide for the health security of approximately 200 million citizens. Our collaboration with international partners (including the WHO, Africa CDC, West African Health Organization, Robert Koch Institute, Public Health England, Resolve to Save Lives, Gates Foundation, World Bank, UK Public Health Rapid Support Team, UNICEF and others) as well as other national public health institutes has helped catalyze the growth of our young agency. However, to build a sustainable and resilient public health institute, national governments must provide majority of its funding.

We all know how quickly an outbreak in 1 country can quickly spread to others. The 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa heightened the need to review the health security architecture of the most affected countries: Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia. Since then, Liberia has established a national public health institute and can provide much-needed country leadership for its own national health security. Sierra Leone is in the process of doing the same. The ongoing Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo highlights the need for a national public health institute that can lead ongoing preparedness and immediate response.

While experts continue to call for action and collaboration in global health, we must remember that the pieces make the whole. The global health community is a collection of sovereign countries, professional groups, multilateral organizations and civil society groups that ultimately have the collective responsibility for addressing the cross-border spread of infectious diseases. But the most important entity in this collection is the countries.

Therefore, it is through developing and strengthening systems in countries that our goal for a safe and secure world can be achieved. Our relationship with Public Health England is a great example of a mutually beneficial North-South collaboration.

Clearly, there can be no global health security without national health security.

Chikwe Ihekweazu (@Chikwe_I; @NCDCgov) is Director-General of the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control.

Indonesian authorities check body temperatures of airline passengers on May 15, 2019 after a Nigerian man infected with monkeypox was diagnosed in Singapore. (Image: Aditya Irawan/NurPhoto via Getty Images)