Lessons on Tackling Online Misinformation During Outbreaks

Public health agencies confronted by the threat of online misinformation might already possess low-cost solutions to tackle it. They just need to reinforce some traditional tenets of risk communication and upgrade others.

This was the main lesson to emerge from our experience producing The Batsapp Project, a documentary podcast on outbreak misinformation. The series chronicles how the public health establishment in Kerala, India wrestled with viral online misinformation during the 2018 Nipah outbreak—which claimed the lives of 17 of the 19 individuals who were infected. We interviewed clinicians, health officials, senior administrators, journalists and activists at the forefront of the Nipah response.

Their stories revealed 5 insights of particular relevance to local public health establishments in low- and middle-income countries seeking to combat online misinformation in relatively resource-constrained contexts:

Monitor social media manually and through crowdsourcing: Kerala’s response team monitored Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp for misinformation and relayed their findings to administrators who would then counter these false claims during daily press briefings. Community members could also verify the accuracy of the messages they received via social media apps by sending it to a publicly distributed mobile number.

Provide psychological support to cope with the outbreak and misinformation: Besides fueling mistrust, anxiety and panic among the general public, misinformation triggers social stigma, ostracization and discrimination against health care workers, their families and the families of victims. In anticipation of the psychological consequences, the district public health establishment in Kerala organized in-person and telephone support through local psychologists and psychiatrists. These sessions involved counseling and relaxation techniques to help affected community members and health workers cope with the situation, and have been revived at a larger scale for COVID-19.

Leverage trust in physicians: Trust is the cornerstone of effective risk communication and clinicians are usually among the most trusted sources of health information. In Kerala, a group of physicians with a substantial social media following formed Infoclinic, an initiative that provides reliable health information and actively partakes in efforts to dispel health-related rumors and misinformation. Infoclinic sought to complement the efforts of the state government by using social media to disseminate accurate health information in the state’s local language, Malayalam.

Bring local leaders together on a common platform: Online misinformation can polarize communities. Kerala’s public health establishment forged a dialogue by bringing together local religious leaders, officials from the local municipality and district administration, and clinicians and allowed journalists to observe these discussions. These dialogues aligned all stakeholders on the outbreak response, including the types of misinformation circulating on social media. This helped create an environment of trust and enabled community and religious leaders to diffuse official and accurate messages to their social networks.

Engage news media, ensure transparency: Traditional news media like newspapers can spread misinformation that originates on online platforms. To minimize this prospect, Kerala’s administrators organized Nipah workshops for journalists, made themselves available for interviews, leveraged existing relationships with editors, and organized daily press conferences. These strategies helped cultivate the news media as a force that was keen to aid the state’s efforts in combating both the disease and misinformation outbreaks.

It might not be feasible to implement all these strategies in all contexts given variations in internet connectivity and access, political trust, religious polarization, and relationships between the news media and the state. However, they demonstrate that misinformation during outbreaks can be tackled using low-cost approaches and by optimizing existing social capital between the public health establishment and local stakeholders.

You can listen to the full story of Kerala’s response to online misinformation and expert perspectives on the psychological dimensions of the global infodemic problem on iTunes, Spotify , SoundCloud, and Google Podcasts. The podcast series was funded by the UK Digital Economy Crucible.

Santosh Vijaykumar, PhD is senior lecturer and public engagement lead at the Department of Psychology, Northumbria University in Newcastle, UK. His research examines the role of social media in global health with a focus on online misinformation during infectious disease outbreaks. He can be reached via Twitter @percer or email: [email protected].

For the latest, most reliable COVID-19 insights from some of the world’s most respected global health experts, see Global Health NOW’s COVID-19 Expert Reality Check.

Join the tens of thousands of subscribers who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues: https://www.globalhealthnow.org/subscribe

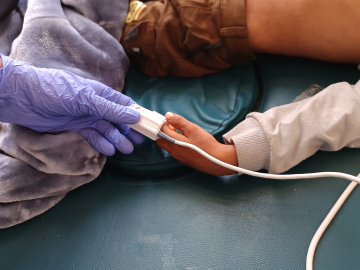

Indian residents wear face mask outside the Medical College hospital in Kerala, India on May 21, 2018, during a Nipah virus outbreak. Image: AFP via Getty