Helping Doctors Reach Rural India

India has a starkly inequitable disease burden in rural and urban areas.

One key contributor: Staff shortages in the health workforce—particularly doctors—in rural India. Rural areas account for 68-71% of India’s population, but are served by just 34% of the country’s doctors.

Solving this deficit of rural doctors comes with ethical and pragmatic challenges. Doctors—highly educated and skilled professionals—are often apprehensive of practicing in rural areas. Often, these posts equate to lower pay, reduced educational and professional opportunities, inadequate infrastructure, limited family support, reduced job satisfaction, and bureaucratic hindrances, among other challenges.

Policies for increasing recruitment and retention of rural doctors should focus on these interconnected issues.

But unfortunately, various state governments have instead subscribed to one-size-fits-all policies: mandating periods of rural service-ships—known as ‘bond’—with heavy financial penalties for non-compliance and non-completion. Bonding has failed repeatedly as a good short-term solution. It also fails to address long-term retention issues; doctors who cannot afford the bond penalty complete their mandatory service, with no intention of serving long-term in rural public health system. Others sidestep the obligation through hefty payments as high as ₹5,000,000 (equivalent to $65,000) in the case of specialist doctors, with smaller payments for MBBS graduates. The bonding approach has been criticized for its paternalistic outlook infringing upon the autonomy of medical graduates and young doctors.

Increasing the number of doctors in rural areas can help solve one India’s biggest health disparity challenges. But first, doctors must be empowered as critical stakeholders.

We propose primary policy solutions that focus on motivating doctors to engage in rural service, not mandating it.

- Medical colleges and associated partners (medical councils and boards) should identify new graduates interested in rural service to become champions for the cause. These ambassadors can then spread the word to their peers about the value of rural service. Harnessing the influence of graduates’ own networks has a better chance of effecting long-term changes in recruitment and retention than punitive bonds. Testimonials by current members of the Association of Rural Surgeons of India show that this approach is realistic and scaleable.

- Commit to long-term investment in rural doctors rather than short-term incentives (such as one-year bonuses and initial benefits). Need and merit-based scholarships should be awarded for educational and professional advancement activities of doctors serving in rural regions. Funds for their children’s education and opportunities for spouses are crucial for retaining rural doctors. Such provisions would not be any different from those currently made for family members of government officials (armed forces officers, railway officers, etc.) serving in remote regions.

- Encourage rural doctors to take on leadership roles, and increase coordination between rural doctors and community stakeholders such as local public health authorities and private vendors. Doctors should administer essential local resources, particularly for health programs, in keeping with local needs. This would be a departure from the current approach, wherein state authorities (mostly non-medical bureaucrats) decide which health conditions are prioritized in a given area, often failing to understand the nuances of local demands. This solution is highly cost-effective, only requiring a reallocation of already available resources. A more significant role in decision-making would pay dividends, increasing doctors’ sense of ownership in their practice and helping them gain patients’ trust. Moreover, online inventories and grievance redressal registries can increase involvement without increasing doctors’ workload.

- Introduce an online portal to showcase all available rural placement options, allowing applicants to choose based on their needs and preferences. Another reason doctors hesitate to work in rural areas is the slow and corrupt bureaucracy that underpins the selection and placement process, which currently requires applicants to visit multiple governmental offices across cities, without any real say in their placement. We propose instead a transparent, online recruitment process. The portal would also serve as a mechanism against corruption and favoritism. Bettering the process of recruitment can also enhance the number and quality of applications.

Choosing policies that empower health workers can help ensure better health for the nation’s people, no matter where they live.

Siddhesh Zadey BSMS is a graduate student in global health at Duke University.

Sweta Dubey MBBS is an independent medical practitioner in India who has previously worked at secondary and tertiary public health centers and completed her rural service under the 'bond.'

The authors are co-founders of a research nonprofit based in India named the Association for Socially Applicable Research.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues: https://www.globalhealthnow.org/subscribe

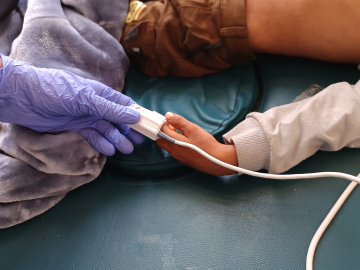

Medical students and doctors demonstrate against the government's decision to make rural posting compulsory for those applying for post-graduation entrance exams. New Delhi, August 8, 2013. Image: Vipin Kumar/Hindustan Times