Flipping the Switch on Stigma

Virtually all Americans know someone who has fallen to opioids.

And if you don’t, “This movie is coming to a theater near you, whatever your politics, whatever your color,” former President Bill Clinton warned yesterday at a forum at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Opioid overdoses reached an all-time high in 2016—and the number is predicted to rise this year. About 64,000 people died from drug overdoses in the US, according to provisional data from the CDC. “If the data is confirmed,” Clinton said, “that means last year more people died of opioid-related drug overdoses than died at the peak of the pre-treatment AIDS crisis.”

Opioids are now the leading cause of death for Americans under age 50, he said.

The good news is that we’re treating this epidemic like a public health problem instead of a criminal justice problem, Clinton said. “From the White House to the smallest farm, [everyone recognizes] this is a very big problem, and lots of good people are working on solutions.”

The bad news, according to Clinton, is that the response so far is not very well-organized, nor well-funded.

Co-hosted by the Clinton Health Matters Initiative, the forum aimed to surface practical and specific solutions, leading with the release of a new report from the Clinton Foundation and the Bloomberg School, America’s Opioid Epidemic: From Evidence to Impact. The report frames a public health response to the epidemic, setting out 10 priority guidelines including monitoring prescriptions, expanding coverage of and accessibility to proven interventions like naloxone, and combatting stigma.

The forum pulled together public health experts, policymakers, law enforcement, and advocacy groups to discuss how to implement and scale up proven evidence-based strategies to prevent and treat opioid addiction and overdose. The causes of the crisis are complex, said Ellen J. MacKenzie, PhD, MSc, dean of the Bloomberg School, but include unsafe prescribing practices, a growing supply of heroin (which is increasingly contaminated with fentanyl) and the fact that far too few people have access to evidence-backed addiction treatment. "Despite recent announcements by the White House, our country has not addressed the real need for urgent action and a true commitment of resources," she said.

President Trump declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency last week—a good first step, said panelist Congressman Elijah Cummings. He praised bipartisan acknowledgement of the opioid crisis, but said resistance to bold action persists in both the White House and Congress. Trump’s declaration doesn’t unlock additional funding, which is critical because people on the frontlines can’t afford to stock up on naloxone, Cummings said.

Public health advocates need to press policymakers to expand naloxone distribution and reduce the cost, preserve programs like Medicare, and push insurance companies to eliminate bias in favor of opioid-based painkillers. It’s a test for our entire society, he said, highlighting John Delaney’s words: “The cost of doing nothing is not nothing.”

Baltimore City Health Commissioner Leana Wen, MD, MSc, FAAEM, described how naloxone has helped her city. After she issued a blanket prescription for naloxone, Baltimore has trained 30,000 people in the use of the drug to reverse overdoses. In the last 2 years, residents have saved 1,500 lives, she said—but it’s not enough; she now has to ration naloxone.

Asked by Clinton what happened to the 1,500 people saved, Wen said many were referred to treatment programs; but there is not nearly enough treatment capacity: Only 1 in 10 can get treatment nationwide.On that point, Cummings said we need to convince policymakers not to reduce Medicaid funding. “Policymakers cry at funerals on the 6 o’clock news— but they get amnesia when it comes to committing the resources,” he said.

In addition to expanded resources for treatment, Clinton emphasized the importance of education. He shared a personal story about a family friend who died because he didn’t know that if you mixed alcohol and opioids could be fatal.

He asked Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, what else we can do on that front. She agreed that education is imperative, but said it has to be coupled with a quick intervention like naloxone to succeed. The pressure on policymakers comes with education, she said, adding, “I also couple it with a stick— there are a lot of worker pension funds invested in big pharma. We’re starting to do what the New Yorker mag did this week too—public pressure to reduce cost of interventions.” And, importantly, "We have to flip switch on stigma," she said.

Tom Geddes, CEO of Plank Industries, discussed the role that doctors can play as well. He called out hospitals for telling patients that their comfort is the priority and said that is sometimes unrealistic—the recovery is the priority. Recounting his wife’s special effort to get off painkillers quickly after a surgery, he noted her doctor’s words: “You just had a hip replacement—you should be managing your pain to a 7, not a 0.”

Wen shared her perspective as a doctor as well. “I’ve overprescribed opioids and not realized. I didn’t learn about the addiction risk in med school. We are trained to take away pain. That tide is turning … we’re training doctors in Baltimore on the addictive potential of opioids, to reduce trend of overprescribing.” That’s the supply side, she said—but the demand side will persist, too, unless we get people the treatment they need when they’re ready for it.”

A second panel also examined the need to frame a public health response and fight stigma, pulling in perspectives from social justice and law enforcement, the medical community and parents affected by the crisis.

Moderated by Michael Botticelli, MEd, former director of National Drug Control Policy, the panelists included Tom Synan, police chief of Newtown, Ohio, who emphasized that the user has a disease. “We’re angry at the user … not the dealer arrested 7-8 times, or the pharmaceutical company that lied to doctors. Our anger is displaced … if we put it where it should be we could fix the problem. We should be angry at the people who do it for greed.”

Botticelli’s response drew applause from the audience: “I love it when our law enforcement officers talk like public health commissioners.”

You can see the webcast of the event here.

Join the thousands of subscribers who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues: http://www.globalhealthnow.org/subscribe.html

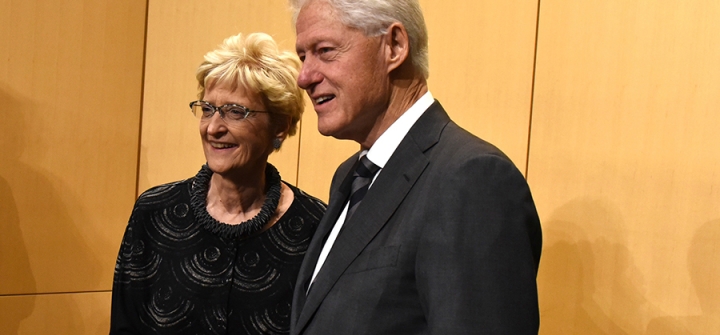

Dean Ellen J. MacKenzie, PhD '79, MSc '75, with former US President Bill Clinton at yesterday's summit: America’s Opioid Epidemic: From Evidence to Impact. Image by Larry Canner.