Who Should Lead Global Health?

With a new president in the White House, many expect the US to reclaim its position as a leader in global health. But this begs an important question.

Should any one nation, especially from the Global North, presume to lead global health?

There is more to the answer than a simple yes or no. Behind the question lurks a set of assumptions and contradictions about North/South relationships that need to be urgently challenged as we enter the Biden-Harris era.

The most egregious forms of power imbalance in global health practice (such as outright human rights violations for the sake of “population control”, including USAID-supported mass sterilizations campaigns in countries like Colombia, Brazil, and Kenya in the 1970s and 1980s) are for the most part, a thing of the past. But the persistence of neocolonial practices still plagues our field.

Whose voices are heard, what knowledge systems are valued, who sits at the decision-making table, and where most of the funds are held are present manifestations of how Global North vertical leadership remains rooted in perceived superiority. Take for example the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, 2 vital funding channels for the global health agenda. Never has there been a president of these institutions that come from the Global South (in fact 12 of the 13 presidents of the World Bank have been from the U.S. and only one a woman), and voting power within these funding agencies is disproportionately skewed to favor rich countries.

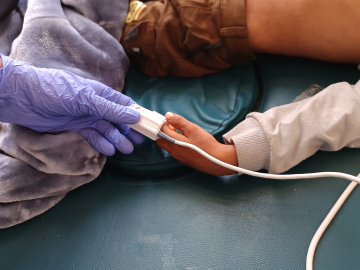

Practices such as these only serve to reinforce laws, policies, and norms that create unequal power dynamics between and within countries. This ultimately leads to the detriment of health outcomes. Inequity will always beget inequity. The growing health gap between income groups during the Covid-19 pandemic all over the world, but especially in countries that already had a baseline unjust social structure (such as the US) should serve as a lesson for our future selves.

Further enhancing unequal power structures is the fact that global health practice is embedded within a larger political agenda. Even the most well-intentioned global health practitioners must recognize that global health partially serves as a geopolitical instrument. Global health funding and programming have consistently been tied to US politics and foreign policy interests. The global-gag rule that erodes women’s reproductive health choices, the decision to retire from the Paris Accord that disproportionately hurts the health of vulnerable populations, and the stringent protection of intellectual property rights by the US that undermine access to essential medicines are only a few examples of the wider political agenda at work.

Only by critically examining the ulterior motives behind global health actions can we move towards a paradigm shift from a top-down, self-interest-focused global health field to a horizontal, collaborative, equity-centered global health practice.

In practice, this necessitates reimagining long-held narratives and power structures in broader development practice. If the US wants to lead global health, it should start by taking a step back, not a step forward. Instead of seeing themselves as leaders, countries like the US should understand their role as catalyzers and enablers of change. They must contribute to the creation of sustainable structures and systems for communities that focus on agency and dignity.

Centering global health strategies, policies, and programs around agency and dignity means strengthening local civic participation, consolidating democratic processes, and improving local/global governance and accountability structures. The approach also means moving beyond the long-held scarcity narrative that depicts lower- and middle-income countries as poor, cursed by corruption, disease-ridden, and instead, recognizing and leveraging local capacities, assets, and strengths. It means incorporating the community as an essential part of the solution rather than as part of the problem.

Working with and not working for emphasizes a widely touted development mantra. With equity as a guiding principle, global health could then be understood as the necessary actions that promote people worldwide taking control of their own health. This would allow communities to reclaim their rights while enabling development partners to meet their responsibilities. Only then will communities around the world have meaningful ownership and leadership roles in the actions that affect their health.

Who should lead global health? Communities. No one else should be able to claim that right over them.

Carlos A. Faerron Guzmán, MD, MSc, directs the Centro Interamericano de Salud Global in Costa Rica and is an assistant professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, Graduate School.

For the latest, most reliable COVID-19 insights from some of the world’s most respected global health experts, see Global Health NOW’s COVID-19 Expert Reality Check.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues: https://www.globalhealthnow.org/subscribe

US President Joe Biden signs executive orders as part of the COVID-19 response. Washington, DC, January 21, 2021. Image: Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty