Keeping the Lights on in Syria

The pandemic strained even the most placid of countries, but health workers in Syria, still in the grips of conflict, faced extra challenges—from daily power outages to cut-off communication, travel, and supply lines.

However, decreased tourism traffic because of the ongoing conflict helped buy hospitals time to prepare—which they did not squander. NGOs also stepped up to fill in gaps in services and help educate the public. The Syrian people largely did their part, too, by listening and respecting public health advice.

Still, many health professionals lost their lives to the virus—a terrible blow to the country, says Alaa Hamdan, a medical student and junior clinical researcher who was nearing the end of her studies when COVID-19 hit Syria.

Hamdan is on track to finish her medical degree this coming November from Tishreen University & Hospital—Syria’s third-largest university, in the port city of Latakia, in the northwestern part of the country. Between long shifts at the hospital and frequent power outages, she shared with GHN what it has been like to be a medical student during a pandemic in this latest installment of GHN’s COVID Countries series.

Syria

Data & Accuracy of Reported Numbers

- Reported Cases/Deaths

- 25,686 Cases

- 1,889 Deaths

- 108,276 vaccine doses administered

(Source: Johns Hopkins University, as of July 7, 2021)

The Big Picture

When the pandemic started, I was a fifth year medical student, attending university lectures and clinical lessons in the hospital. In my country, many places were affected, but the situation has been the most tragic in Damascus, the capital. The cases were much higher than here, in Latakia, due to the larger population and volume of traffic. But in terms of deaths, I don't think that we have the same numbers or the same severity other countries face.

The government, fortunately, responded early enough to prevent a big problem, closing shops, universities, schools, official public services, restaurants and crowded public places. At first, the restrictions were extensive—closures for entire days at a time, for example. After a while, though, the economic hardship was too much, with people who have little choice but to work every day losing out on their source of income. So official public services reopened, but at reduced capacity.

As for the hospitals, they were well prepared, actually. Medical professionals here were in contact with others outside Syria early on, and had a good picture of what to watch out for, what symptoms to look for. A central committee from the Ministry of Health was established to look for the latest information and to pay close attention to the general situation in and outside the country. So, they had strategies in place to screen people (emergency response) by phone to guide people and limit them from heading directly to hospitals.

We also reorganized hospitals, dedicating some for isolation to help reduce the number and contacts between Covid patients and others. But the other thing is, they didn't get overloaded with too many patients at one time—and that’s because we had some time to prepare the hospital. Another factor working in Syria’s favor was that because of the ongoing conflict, there isn’t a lot of tourism travel in and out of the country.

NGOs played a big part in supporting health workers and spreading awareness about the risks, which helped prevent an even bigger disaster. The Red Cross/Red Crescent and MedDose, a civil society organization, for example, provided a lot of services and education, urging people to take the pandemic seriously. They also established an urgent care service, with a hotline staffed 24 hours a day by doctors, medical students, and nurses. They helped coach people through various situations, such as determining whether a sick family member could be managed outside the hospital. Nurses even made house calls in some cases. They also helped provide families with oxygen canisters when needed. All of these efforts helped us reduce pressure on the hospital.

Data Dive

The first week of the pandemic here, (May 21, 2020) there was no available data and health professionals and everyone in the hospitals had to act on very, very little information.

Now, hospitals have been documenting patients with COVID. However, it is still hard to obtain data, which we realized trying to undertake research on COVID-19 case narrations, part of a global and local collaborative research effort my university is involved in as well as local projects aiming to investigate the impact of COVID-19 on health care. During the pandemic, we’ve been collecting data from across Syria describing case characteristics. Now, we are applying for access to official data. It is still a sensitive issue and officials will want to review the figures; they want to know where this data will be used. But we hope to present research about the characteristics of this pandemic in Syria and how we responded very soon.

The Hardest Part

I think the most difficult challenge has been ensuring the protection of health workers. We lost many medical professionals—including a lot of doctors who were very, very experienced, or skilled in various specialties—and that has been one of the most devastating things. I don't think we have official data for the doctors who have died, but I think it's a fairly large number—more than 50, just in the major hospitals in Syria.

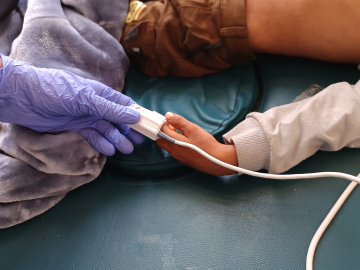

Medical workers on the frontlines had very limited protective gear during the worst periods. As happened in many countries, they had to reuse protective equipment—including masks. Some medical residents, especially in the beginning, were buying their own masks because doctors just didn’t have enough masks and PPE.

The People Get It

We’ve been pleasantly surprised at the level of awareness and adherence to the rules, especially given the enormous economic pressure people feel to continue working. Syrians are very much following all the rules in public places, such as social distancing and masks.

I think people support these rules because they understand the limits of our health care system and hospitals. They are afraid of the risks if they end up having to go to the hospital. The main messaging that helped was, if people don't want to die, they have a lot of information in front of them and if they stick to the rules, they should be fine.

NGOs were also very helpful in spreading awareness, showing the people what was happening in neighboring countries and encouraging them to pay attention to the rules.

The Vaccine Situation

A couple of months ago, different vaccines arrived, and they are now available through the Ministry of Health via public registration. Residents and medical students are also receiving their vaccines now. The rollout has been orderly so far; you have to make a reservation and you’re given a date. Medical professionals are first in line; my friends working as residents have already received it. Older people are next in line. But everyone in Syria is able to go ahead and register. It will take time to get to everyone, but it's ongoing.

We are now working on another aspect—spreading awareness to encourage people to take the vaccine. It’s not required, but in our role as medical professionals and students, we’re trying to explain that vaccines can help reduce cases and hospitalizations—and ease the burden on the health system.

We’ve definitely had problems with people with no expertise spreading misleading information on social media and elsewhere—not just about vaccines, but other aspects of the pandemic, too. In additional to NGOs, medical professionals—including medical students—are respected by society and have jumped in to help efforts to shut down misinformation.

Remote Learning: Unplugged

Schools have been mostly closed, since about May of 2020. But this has been harder for Syria than some countries, because we don’t have a strong structure for remote learning. Online learning does not work well here. Wi-Fi is available in most places, but it isn’t always affordable. The bigger problem is electricity, which is only on a few hours a day. It’s generally 4 hours off, 2 hours on—giving us about 6 hours a day to do everything relying on electricity.

It’s our everyday situation, we’re used to it—and it affects health workers and researchers too. Hospitals have electricity available all the time—but it’s a huge impediment for researchers trying to stick to deadlines and keep laptops charged. We’ve been looking into alternatives relying on solar technology.

The Healing Power of Music

I’ll never forget the story of one man, around 75 years old, who wound up in the hospital with COVID-19. Everyone was worried he would die, given his age and condition, but he was genuinely at peace, not sad or upset. He brought a guitar with him that he played in the hospital.

The doctor treating him became very attached to him, and feared the worst. But slowly, his lungs starting to heal, and he kept improving—and he made it. After he recovered, he told the doctor that he saw how sad he was, and how much you tried to prepare him and his family to cope, but he did not lose hope. And as a thank you, he gave his guitar to the doctor.

Ed. Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

A Syrian man wearing a face mask walks in front of COVID-19 posters, Damascus. April 1, 2020. Image: Louai Beshara/AFP/Getty