Humility: A Global Health Professional’s Most Important Attribute

When I was 3, India opened up its economy, bringing in companies from around the world. Everything changed. As a baby, I had cloth diapers. My younger brother wore disposable diapers.

This era of globalization gave me my first taste of Western hegemony and its influence. Everything about Western civilization fascinated me. Distinctly aware of my skin color, I tried to be as fair as possible. I insisted on liking Coca-Cola more than Rooh Afza, Cadbury more than rasgulla, and pizza more than dal bhaat. I thought Tom Cruise was the most handsome man and Julia Roberts had the prettiest smile.

After medical school, I ended up in the US. But it seemed my lifelong drive to become Western wasn’t enough. Despite all my attempts to be a “white” Western man, I was a brown Indian in the US. Even after 4 years, I sometimes felt like America never really accepted me.

I returned to India after residency and began working at Jan Swasthya Sahyog, in Bilaspur. There, I attended a meeting on building high-quality health systems. The conference, held in a swanky building in posh South Delhi, followed the publication of a major study on the same topic.

One of the study’s suggestions, to limit deliveries to facilities capable of performing Caesarean sections, became a flashpoint of debate in my group. The paper’s lead author, a white academic and the only outsider, led, moderated, and dominated the discussion. Representatives from more developed states in India agreed with her, while those from less-developed states, like mine, suggested continuing with the current delivery practices.

The author pushed hard in favor of changing the paradigm, presenting strong arguments drawing on evidence from Malawi, Thailand and Mexico—which she said India could learn from. One of the local academics disagreed and tried explaining to her about India’s unique situation. I shared my view that the policy could be dangerous if not piloted at a small scale. Ultimately, the group voted against changing the paradigm.

While we may have won that debate, it felt like we had been colonized. Not because of the way the author presided over the meeting or because she did something offensive, but because of the sheer power dynamic in the room. As an Ivy League academic, she could produce all sorts of research and stats from the unending resources at her disposal that I felt we’d never be able to match. Even if she lost the vote, I felt that she still had the power to change policies in India.

A few months later, I went to Cestos, Liberia—a beautiful beach town by the Atlantic Ocean with warm, welcoming people. Working with Last Mile Health to help strengthen Liberia’s community health program, I shared an office with the Liberian government’s county health team.

Liberia not only welcomed me, it gave me what the US could not—something I’d been chasing since childhood. While the US turned me from fair to brown, Liberia made me a “white man.” In Liberia, I wasn't an immigrant; I was an expat. It felt strange to be the white man.

During meetings with Liberians, I often wondered, how will I be perceived? Will they see me as I saw the Ivy League academic? It seemed that my powers increased as the perception of my skin got fairer. My skin color shaped my experience. Our history and our oppressive social structures like racism, casteism, classism, elitism, and patriarchy decide these vulnerabilities and privileges. In these meetings, I struggled with these thoughts, and I was too cautious to speak—conscious that I had very little context of Liberia.

In my discomfort, I tried to imagine how we might dismantle these forces to create an equitable society.

During my initial global health fellowship training, I was taught to keep in mind the principles of equity, solidarity and humility. Yet my time in Liberia was such an unequal experience; I can never give back what I gained there. How do equity and solidarity look in such a situation, I wondered? How should one communicate with local health teams? I learned that if there is one skill I need to cultivate, it is humility.

Humility is that uneasy awareness that you are in many ways still an outsider, you do not have the full context or lived experience of another being, and you do not have all the right answers.

Humility is the feeling that should make you pause and listen fully before contributing.

Anup Agarwal, MBBS completed a global health fellowship with the HEAL Initiative at the University of California, San Francisco, following his residency in Internal Medicine. As part of his fellowship, he spent time with Jan Swasthya Sahyog in Bilaspur, India and Last Mile Health in Liberia.

Join the thousands of subscribers who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues: http://www.globalhealthnow.org/subscribe.html

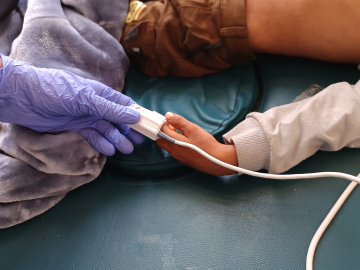

A paramedical teacher in Kolkata, India instructs students on how to draw blood. © 2015 Dipayan Bhar, Courtesy of Photoshare